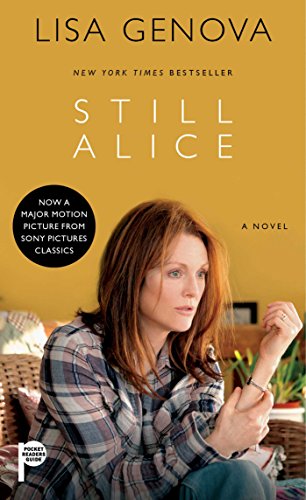

Still Alice - Softcover

Synopsis

From New York Times bestselling author and neuroscientist Lisa Genova comes the definitive—and illuminating—novel about Alzheimer’s disease. Now a major motion picture starring Oscar winner Julianne Moore! Look for Lisa Genova's latest novel Inside the O’Briens.

Alice Howland is proud of the life she worked so hard to build. At fifty years old, she’s a cognitive psychology professor at Harvard and a world-renowned expert in linguistics with a successful husband and three grown children. When she becomes increasingly disoriented and forgetful, a tragic diagnosis changes her life—and her relationship with her family and the world—forever. As she struggles to cope with Alzheimer’s, she learns that her worth is comprised of far more than her ability to remember.

At once beautiful and terrifying, Still Alice is a moving and vivid depiction of life with early-onset Alzheimer’s disease that is as compelling as A Beautiful Mind and as unforgettable as Ordinary People.

"synopsis" may belong to another edition of this title.

About the Author

Acclaimed as the Oliver Sacks of fiction and the Michael Crichton of brain science, Lisa Genova is the New York Times bestselling author of Still Alice, Left Neglected, Love Anthony, and Inside the O’Briens. Still Alice was adapted into an Oscar-winning film starring Julianne Moore, Alec Baldwin, and Kristen Stewart. Lisa graduated valedictorian from Bates College with a degree in biopsychology and holds a PhD in neuroscience from Harvard University. She travels worldwide speaking about the neurological diseases she writes about and has appeared on The Dr. Oz Show, Today, PBS NewsHour, CNN, and NPR. Her TED talk, What You Can Do To Prevent Alzheimer's, has been viewed over 2 million times.

Excerpt. © Reprinted by permission. All rights reserved.

Still Alice

SEPTEMBER 2003

Alice sat at her desk in their bedroom distracted by the sounds of John racing through each of the rooms on the first floor. She needed to finish her peer review of a paper submitted to the Journal of Cognitive Psychology before her flight, and she’d just read the same sentence three times without comprehending it. It was 7:30 according to their alarm clock, which she guessed was about ten minutes fast. She knew from the approximate time and the escalating volume of his racing that he was trying to leave, but he’d forgotten something and couldn’t find it. She tapped her red pen on her bottom lip as she watched the digital numbers on the clock and listened for what she knew was coming.

“Ali?”

She tossed her pen onto the desk and sighed. Downstairs, she found him in the living room on his knees, feeling under the couch cushions.

“Keys?” she asked.

“Glasses. Please don’t lecture me, I’m late.”

She followed his frantic glance to the fireplace mantel, where the antique Waltham clock, valued for its precision, declared 8:00. He should have known better than to trust it. The clocks in their home rarely knew the real time of day. Alice had been duped too often in the past by their seemingly honest faces and had learned long ago to rely on her watch. Sure enough, she lapsed back in time as she entered the kitchen, where the microwave insisted that it was only 6:52.

She looked across the smooth, uncluttered surface of the granite countertop, and there they were, next to the mushroom bowl heaping with unopened mail. Not under something, not behind something, not obstructed in any way from plain view. How could he, someone so smart, a scientist, not see what was right in front of him?

Of course, many of her own things had taken to hiding in mischievous little places as well. But she didn’t admit this to him, and she didn’t involve him in the hunt. Just the other day, John blissfully unaware, she’d spent a crazed morning looking first all over the house and then in her office for her BlackBerry charger. Stumped, she’d surrendered, gone to the store, and bought a new one, only to discover the old one later that night plugged in the socket next to her side of the bed, where she should have known to look. She could probably chalk it all up for both of them to excessive multitasking and being way too busy. And to getting older.

He stood in the doorway, looking at the glasses in her hand but not at her.

“Next time, try pretending you’re a woman while you look,” said Alice, smiling.

“I’ll wear one of your skirts. Ali, please, I’m really late.”

“The microwave says you have tons of time,” she said, handing them to him.

“Thanks.”

He grabbed them like a relay runner taking a baton in a race and headed for the front door.

“Will you be here when I get home on Saturday?” she asked his back as she followed him down the hallway.

“I don’t know, I’ve got a huge day in lab on Saturday.”

He collected his briefcase, phone, and keys from the hall table.

“Have a good trip, give Lydia a hug and kiss for me. And try not to battle with her,” said John.

She caught their reflection in the hallway mirror—a distinguished-looking, tall man with white-flecked brown hair and glasses; a petite, curly-haired woman, her arms crossed over her chest, each readying to leap into that same, bottomless argument. She gritted her teeth and swallowed, choosing not to jump.

“We haven’t seen each other in a while. Please try to be home?” she asked.

“I know, I’ll try.”

He kissed her, and although desperate to leave, he lingered in that kiss for an almost imperceptible moment. If she didn’t know him better, she might’ve romanticized his kiss. She might’ve stood there, hopeful, thinking it said, I love you, I’ll miss you. But as she watched him hustle down the street alone, she felt pretty certain he’d just told her, I love you, but please don’t be pissed when I’m not home on Saturday.

They used to walk together over to Harvard Yard every morning. Of the many things she loved about working within a mile from home and at the same school, their shared commute was the thing she loved most. They always stopped at Jerri’s—a black coffee for him, a tea with lemon for her, iced or hot, depending on the season—and continued on to Harvard Yard, chatting about their research and classes, issues in their respective departments, their children, or plans for that evening. When they were first married, they even held hands. She savored the relaxed intimacy of these morning walks with him, before the daily demands of their jobs and ambitions rendered them each stressed and exhausted.

But for some time now, they’d been walking over to Harvard separately. Alice had been living out of her suitcase all summer, attending psychology conferences in Rome, New Orleans, and Miami, and serving on an exam committee for a thesis defense at Princeton. Back in the spring, John’s cell cultures had needed some sort of rinsing attention at an obscene hour each morning, but he didn’t trust any of his students to show up consistently. So he did. She couldn’t remember the reasons that predated spring, but she knew that each time they’d seemed reasonable and only temporary.

She returned to the paper at her desk, still distracted, now by a craving for that fight she hadn’t had with John about their younger daughter, Lydia. Would it kill him to stand behind her for once? She gave the rest of the paper a cursory effort, not her typical standard of excellence, but it would have to do, given her fragmented state of mind and lack of time. Her comments and suggestions for revision finished, she packaged and sealed the envelope, guiltily aware that she might’ve missed an error in the study’s design or interpretation, cursing John for compromising the integrity of her work.

She repacked her suitcase, not even emptied yet from her last trip. She looked forward to traveling less in the coming months. There were only a handful of invited lectures penciled in her fall semester calendar, and she’d scheduled most of those on Fridays, a day she didn’t teach. Like tomorrow. Tomorrow she would be the guest speaker to kick off Stanford’s cognitive psychology fall colloquium series. And afterward, she’d see Lydia. She’d try not to battle with her, but she wasn’t making any promises.

ALICE FOUND HER WAY EASILY to Stanford’s Cordura Hall on the corner of Campus Drive West and Panama Drive. Its white stucco exterior, terra-cotta roof, and lush landscaping looked to her East Coast eyes more like a Caribbean beach resort than an academic building. She arrived quite early but ventured inside anyway, figuring she could use the extra time to sit in the quiet auditorium and look over her talk.

Much to her surprise, she walked into an already packed room. A zealous crowd surrounded and circled a buffet table, aggressively diving in for food like seagulls at a city beach. Before she could sneak in unnoticed, she noticed Josh, a former Harvard classmate and respected egomaniac, standing in her path, his legs planted firmly and a little too wide, as if he was ready to dive at her.

“All this, for me?” asked Alice, smiling playfully.

“What, we eat like this every day. It’s for one of our developmental psychologists, he was tenured yesterday. So how’s Harvard treating you?”

“Good.”

“I can’t believe you’re still there after all these years. You ever get too bored over there, you should consider coming here.”

“I’ll let you know. How are things with you?”

“Fantastic. You should come by my office after the talk, see our latest modeling data. It’ll really knock your socks off.”

“Sorry, I can’t, I have to catch a flight to L.A. right after this,” she said, grateful to have a ready excuse.

“Oh, too bad. Last time I saw you I think was last year at the psychonomic conference. I unfortunately missed your presentation.”

“Well, you’ll get to hear a good portion of it today.”

“Recycling your talks these days, huh?”

Before she could answer, Gordon Miller, head of the department and her new superhero, swooped in and saved her by asking Josh to help pass out the champagne. As at Harvard, a champagne toast was a tradition in the psychology department at Stanford for all faculty who reached the coveted career milestone of tenure. There weren’t many trumpets that heralded the advancement from point to point in the career of a professor, but tenure was a big one, loud and clear.

When everyone was holding a cup, Gordon stood at the podium and tapped the microphone. “Can I have everyone’s attention for a moment?”

Josh’s excessively loud, punctuated laugh reverberated alone through the auditorium just before Gordon continued.

“Today, we congratulate Mark on receiving tenure. I’m sure he’s thrilled to have this particular accomplishment behind him. Here’s to the many exciting accomplishments still ahead. To Mark!”

“To Mark!”

Alice tapped her cup with her neighbors’, and everyone quickly resumed the business of drinking, eating, and discussing. When all of the food had been claimed from the serving trays and the last drops of champagne emptied from the last bottle, Gordon took the floor once again.

“If everyone would take a seat, we can begin today’s talk.”

He waited a few moments for the crowd of about seventy-five to settle and quiet down.

“Today, I have the honor of introducing you to our first colloquium speaker of the year. Dr. Alice Howland is the eminent William James Professor of Psychology at Harvard University. Over the last twenty-five years, her distinguished career has produced many of the flagship touchstones in psycholinguistics. She pioneered and continues to lead an interdisciplinary and integrated approach to the study of the mechanisms of language. We are privileged to have her here today to talk to us about the conceptual and neural organization of language.”

Alice switched places with Gordon and looked out at her audience looking at her. As she waited for the applause to subside, she thought of the statistic that said people feared public speaking more than they feared death. She loved it. She enjoyed all of the concatenated moments of presenting in front of a listening audience—teaching, performing, telling a story, teeing up a heated debate. She also loved the adrenaline rush. The bigger the stakes, the more sophisticated or hostile the audience, the more the whole experience thrilled her. John was an excellent teacher, but public speaking often pained and terrified him, and he marveled at Alice’s verve for it. He probably didn’t prefer death, but spiders and snakes, sure.

“Thank you, Gordon. Today, I’m going to talk about some of the mental processes that underlie the acquisition, organization, and use of language.”

Alice had given the guts of this particular talk innumerable times, but she wouldn’t call it recycling. The crux of the talk did focus on the main tenets of linguistics, many of which she’d discovered, and she’d been using a number of the same slides for years. But she felt proud, and not ashamed or lazy, that this part of her talk, these discoveries of hers, continued to hold true, withstanding the test of time. Her contributions mattered and propelled future discovery. Plus, she certainly included those future discoveries.

She talked without needing to look down at her notes, relaxed and animated, the words effortless. Then, about forty minutes into the fifty-minute presentation, she became suddenly stuck.

“The data reveal that irregular verbs require access to the mental . . .”

She simply couldn’t find the word. She had a loose sense for what she wanted to say, but the word itself eluded her. Gone. She didn’t know the first letter or what the word sounded like or how many syllables it had. It wasn’t on the tip of her tongue.

Maybe it was the champagne. She normally didn’t drink any alcohol before speaking. Even if she knew the talk cold, even in the most casual setting, she always wanted to be as mentally sharp as possible, especially for the question-and-answer session at the end, which could be confrontational and full of rich, unscripted debate. But she hadn’t wanted to offend anyone, and she’d drunk a little more than she probably should have when she became trapped again in passive-aggressive conversation with Josh.

Maybe it was jet lag. As her mind scoured its corners for the word and a rational reason for why she’d lost it, her heart pounded and her face grew hot. She’d never lost a word in front of an audience before. But she’d never panicked in front of an audience either, and she’d stood before many far larger and more intimidating than this. She told herself to breathe, forget about it, and move on.

She replaced the still blocked word with a vague and inappropriate “thing,” abandoned whatever point she’d been in the middle of making, and continued on to the next slide. The pause had seemed like an obvious and awkward eternity to her, but as she checked the faces in the audience to see if anyone had noticed her mental hiccup, no one appeared alarmed, embarrassed, or ruffled in any way. Then, she saw Josh whispering to the woman next to him, his eyebrows furrowed and a slight smile on his face.

She was on the plane, descending into LAX, when it finally came to her.

Lexicon.

LYDIA HAD BEEN LIVING IN Los Angeles for three years now. If she’d gone to college right after high school, she would’ve graduated this past spring. Alice would’ve been so proud. Lydia was probably smarter than both of her older siblings, and they had gone to college. And law school. And medical school.

Instead of college, Lydia first went to Europe. Alice had hoped she’d come home with a clearer sense of what she wanted to study and what kind of school she wanted to go to. Instead, upon her return, she’d told her parents that she’d done a little acting while in Dublin and had fallen in love. She was moving to Los Angeles immediately.

Alice nearly lost her mind. Much to her maddening frustration, she recognized her own contribution to this problem. Because Lydia was the youngest of three, the daughter of parents who worked a lot and traveled regularly, and had always been a good student, Alice and John had ignored her to a large extent. They’d granted her a lot of room to run in her world, free to think for herself and free from the kind of micromanagement placed on a lot of children her age. Her parents’ professional lives served as shining examples of what could be gained from setting lofty and individually unique goals and pursuing them with passion and hard work. Lydia understood her mother’s advice about the importance of getting a college education, but she had the confidence and audacity to reject it.

Plus, she didn’t stand entirely alone. The most explosive fight Alice had ever had with John had followed his two cents on the subject: I think it’s wonderful, she can always go to college later, if she decides she even wants to.

Alice checked her BlackBerry for the address, rang the doorbell to apartment number seven, and waited. She was just about to press it again when Lydia opened the door.

“Mom, you’re early,” said Lydia.

Alice checked her watch.

“I’m right on time.”

“You said your flight was coming in at eight.”

“I said five.”

“I have eight o’clock written down in my book.”

“Lydia, it...

"About this title" may belong to another edition of this title.

- PublisherPocket Books

- Publication date2014

- ISBN 10 1501107739

- ISBN 13 9781501107733

- BindingMass Market Paperback

- LanguageEnglish

- Number of pages400

- Rating

Shipping:

FREE

Within U.S.A.

Buy New

Learn more about this copy

Shipping:

US$ 3.95

Within U.S.A.

Top Search Results from the AbeBooks Marketplace

Still Alice

Seller: Your Online Bookstore, Houston, TX, U.S.A.

Mass Market Paperback. Condition: Good. Seller Inventory # 1501107739-3-18856187

Quantity: 2 available

Still Alice

Seller: Your Online Bookstore, Houston, TX, U.S.A.

Mass Market Paperback. Condition: Fair. Seller Inventory # 1501107739-4-23080666

Quantity: 2 available

Still Alice

Seller: Gulf Coast Books, Memphis, TN, U.S.A.

Mass Market Paperback. Condition: Fair. Seller Inventory # 1501107739-4-20454548

Quantity: 2 available

Still Alice

Seller: Gulf Coast Books, Memphis, TN, U.S.A.

Mass Market Paperback. Condition: Good. Seller Inventory # 1501107739-3-19833865

Quantity: 1 available

Still Alice

Seller: Orion Tech, Kingwood, TX, U.S.A.

Mass Market Paperback. Condition: Fair. Seller Inventory # 1501107739-4-23602202

Quantity: 2 available

Still Alice

Seller: SecondSale, Montgomery, IL, U.S.A.

Condition: Good. Item in good condition. Textbooks may not include supplemental items i.e. CDs, access codes etc. Seller Inventory # 00052287138

Quantity: Over 20 available

Still Alice

Seller: Orion Tech, Kingwood, TX, U.S.A.

Mass Market Paperback. Condition: Good. Seller Inventory # 1501107739-3-18483572

Quantity: 3 available

Still Alice

Seller: SecondSale, Montgomery, IL, U.S.A.

Condition: Good. Item in very good condition! Textbooks may not include supplemental items i.e. CDs, access codes etc. Seller Inventory # 00079244104

Quantity: 1 available

Still Alice

Seller: SecondSale, Montgomery, IL, U.S.A.

Condition: Acceptable. Item in good condition. Textbooks may not include supplemental items i.e. CDs, access codes etc. Seller Inventory # 00044911112

Quantity: 8 available

Still Alice

Seller: SecondSale, Montgomery, IL, U.S.A.

Condition: Good. Good condition ex-library book with usual library markings and stickers. Seller Inventory # 00041089119

Quantity: 1 available